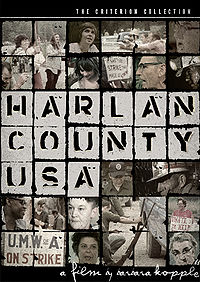

It’s doubtful that Harlan County, USA, is on any tourist guidebook “must visit” lists today. And it certainly wasn’t in 1973, when Barbara Koppel was making this classic social documentary about the struggles of striking coal miners. Just watching the footage, with its Southern drawl, red necks and decaying teeth made me want to move back to Canada. But I stayed in my chair. And I admire Koppel for staying in Harlan County for the years it took to make this important film, and glad she found gold under all that coal when she won an Academy Award when the film was released in 1976.

It’s doubtful that Harlan County, USA, is on any tourist guidebook “must visit” lists today. And it certainly wasn’t in 1973, when Barbara Koppel was making this classic social documentary about the struggles of striking coal miners. Just watching the footage, with its Southern drawl, red necks and decaying teeth made me want to move back to Canada. But I stayed in my chair. And I admire Koppel for staying in Harlan County for the years it took to make this important film, and glad she found gold under all that coal when she won an Academy Award when the film was released in 1976.

Synopsis: Striking union coal miners in rural Kentucky go head-to-head with Duke Power and its “gun thugs” in a lengthy strike that leaves one miner dead. The film illustrations the conditions that miners worked under in the mid-70s, which caused many to suffer black lung and die in mine accidents, and their struggle for decent wages and working conditions. The film, made by Barbara Koppel, also documents the active role played by the miner’s wives in support of the strike. Violent clashes on the picket lines are recorded by filmmakers as well as messy power struggles within the labor union leadership that ultimately leave miners feeling alone in their struggle.

Story structure: Story roughly begins with the strike, follows events during the strike, and concludes when miners signing contract that was less than what many wanted. But along the way, we take many sidebar trips into understanding conditions miners work under, view historical footage of famous mine disasters in the region and meet survivors and relatives who give interviews, and learn about labor politics. It seems the filmmakers set out to make us want to care about the plight of the miners BEFORE it portrayed them as being on strike – and they spend considerable amount of time in beginning of film doing that before we learn they are on strike. Probably chose that approach because of knee-jerk reaction many American’s have against organized labor. There’s no satisfying conclusion to the film, though, when the strike ends: the miners seem resigned to repeating this struggle over and over again.

Cinematography: I’m still wondering how the filmmakers got permission to film in the mine – perhaps the shots that open the film of the miners leaping onto conveyor belts that take them deep into the mine were shot after the strike ended and they returned to work, in non-linear sequence. But I’m still surprised that Duke Power would allow them to film the miners afterward. In any case, the fact they were able to film in the mines is an achievement. Without it, the film wouldn’t have had the same “there but for the grace of god go I” feel.

Because they lived with the affected people over a period of more than a year, they got intimate access which is what’s remarkable about the otherwise unremarkable cinematography in the film. Simply being able to be there with a camera when the grandmother collapses on seeing her grandson’s open casket, for example, is so powerful. The cinematography is very journalistic, but one memorable artistic moment is the shot of miners silhouetted around the barrel fires on the picket lines. Some of the shooting was also quite brave: there’s moments where gun thugs approach the camera menacingly, and you hear Barbara’s voice off-camera talking to them, sounding quite confident and sure of herself.

Editing: The film was cut together using a combination of interviews, archival and news footage, photos, and cinema verite shooting. There’s one very plain textual graphic device used in the film to convey info very effectively: using 3 lines of simple white text over a shot of the mine, the first line shows the percentage increase of Duke Power’s profits. Second line shows miners wages increase. Third line shows cost of living increase. We see that the miners are making less than cost of living increase, while profits were up 170 percent. Very effective; no animation required, just these numbers presented cleanly.

Music and Sound: Since the union miners have a rich tradition of singing, why not use that as the soundtrack of the film? It’s the obvious choice. And sometimes the obvious choice is the best choice. It certainly is very effective in this film. Early in the film we hear a coal mining song being sung in background over shots of mining life. Then we cut to a guy who looks like the face of death, rocking on his porch and we realize he’s actually the guy singing. Nice way to bring the soundtrack to life, and as it turns out, transition into an interview with the man about what it was like for him to work in the mines.

A lot of the tracks are purely vocal, sung without musical accompaniment. Some include banjo picking. All contribute to the ambience of the place as being low education, low opportunity, but big hearted and real.