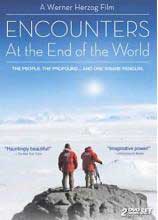

After watching Encounters at the End of the World last night, I think the film’s subtitle should be: filtered through Warner Herzog’s brain, things get strange.

After watching Encounters at the End of the World last night, I think the film’s subtitle should be: filtered through Warner Herzog’s brain, things get strange.

Synopsis: German filmmaker Warner Herzog visits Antarctica, lured by haunting images of divers swimming under the ice shot by a friend. While there he makes some arresting images of his own, and meets some unusual characters, both animal and human. Apparently taking it as an article of faith that humans will one day go extinct as a result of global warming, he trains his camera on what aliens might one day learn about us based on the well-preserved evidence left behind on this beautiful, brutal continent by explorers dating back to Shackleton.

Story and Structure: The film is a personal narrative, a travelogue that follows a roughly chronological structure, beginning with Herzog’s arrival by plane in Antarctica, and concluding somewhere near the end of the trip (we don’t actually see him leave). Herzog narrates the film from beginning to end, explaining why he came here, complete with details about how the film was funded, and what interests him about the place and the people he finds. In between the narrated bits, the story is advanced by interviews with the characters Herzog meets, whom he questions (with his voice clearly audible off camera). The interviews often give way to scenes of the people doing their thing – exploring volcanos, diving under the ice, harvesting seal milk. Herzog supports his story with a few archival clips from Westerns, as well as historical footage from Shackleton’s voyage. And ultimately his story is this: man goes on a quest seeking things, sometimes finding them, sometimes not, but ultimately bearing witness to the incredible misery, mystery and beauty of the universe, which is itself completely impervious to us.

Cinematography: This is a beautiful film. And yet, it’s full of handheld, jerky shots that at first made me think: how come he didn’t steady that? On second thought, it’s perfect – the world as Herzog sees it in this film is imperfect, conflicted, and a less-than-perfect camera work emphasizes this point. Shots that would have used a steadicam or dolly in a slicker production are simply walked into with the camera shoulder carried.

Another interesting thing I observed was that a few of the interviews used direct address: with the subject talking straight into the camera. It’s not a convention, though: many of the interviews are conducted with the person looking off axis. The interview with the Apache plumber is an utterly fantastic example of why great camera operators always leave the camera running after the person appears to be finished speaking: the guy just stands there with his fingers together, and then goes back to work. The camera operator keeps the camera on him. The guy sees the camera is still on him, so he feels the need to perform. He grabs the torch, and says “I call on the spirit of my ancestors! Let there be fire!” It nails his character. Takeaway: Always roll at least a 10 count after you think the shot has ended. Always.

Editing: I like how simple editing conventions are used to get us into the various points in the story: for example, the scene in which the milk is harvested from the seals, opens with the seals being milked. Then we cut to a wide shot of the ice-perched lab where the results are studied. As soon as the shot changes from the seals to the wide shot of the lab, Herzog’s narration begins. Then we cut to a medium shot of the lab. Narration continues, and we cut to a shot inside the lab, where a scientist is preparing the sample for analysis. Narration ends, and the woman’s voice begins: “This was just collected today…” Great storytelling device. We get from there to the next sequence by cutting from face of scientists listening to seals below ice to a close up of a blowtorch being lit by a plumber. The ‘pop’ of the flame igniting is matched with the last ‘pop’ of the seal sounds. Lots of beautiful cuts like this in the film.

Editing interviews: I noticed that reframing on interviews worked well in many cases. That is: Set up the interview, get the person talking. Then reframe between questions (zoom in to medium shot). Also, roll on face of person when they are not talking. That worked great because Herzog had time to finish his narration before the person picks up talking.

Music and Sound: Sounds is very important to creating the mood of this film, and haunting music carries the long underwater sequences and ice cave sequences. But most of the time it’s subtle and in the background, contributing to the mood. Chanting begins and ends the film, always in a different language than English. I watched the film with my friend Oksana, who is from Russia, and she told me the chanting at the end was Orthodox priests chanting in Russian about forgiveness and begging God for mercy. How perfect is that? But for everyone else, it’s just weird chanting with words that might as well be from another planet creating an eerie sense of mystery. One thing that surprised me: there’s virtually no sound of wind in the film, which I would have expected to hear in such a harsh place. Apparently they did a great job blimping the mics, probably a little too good. But the audio is of exceptionally high quality. Also they did a great job recording and incorporating found sound – the scientists who play guitar to celebrate finding a new species, for example.