I wonder how many journalists became journalists because of Hunter S. Thompson? At the student newspaper when I was a journalism student at University of Montana, we’d spend hours debating his style late into the night, usually over beers. But the reality, I quickly discovered at my first newspaper job, is quite different. Journalists generally quietly support the status quo with stories that rarely challenge anything other than our ability to remain interested in what they have to say.

I wonder how many journalists became journalists because of Hunter S. Thompson? At the student newspaper when I was a journalism student at University of Montana, we’d spend hours debating his style late into the night, usually over beers. But the reality, I quickly discovered at my first newspaper job, is quite different. Journalists generally quietly support the status quo with stories that rarely challenge anything other than our ability to remain interested in what they have to say.

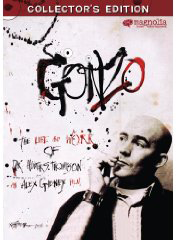

Synopsis: Few journalists have made a greater impact on their readers than Hunter S. Thompson, whose “gonzo journalism” defined a generation from the pages of The Rolling Stone. This film recounts that as well as his less well known life as father, a gun-lover, and a world-class celebrity who ultimately felt trapped by his own success, but who always followed his own eccentric path right up to his suicide in 2005.

Story Structure: Mostly linear and chronological story of his life, but with the frequently used device of beginning at his death, and then skipping back to the beginning, the progressing through his live to end the film at his spectacular funeral. I’m not sure how well this type of beginning works, actually – if there was something cliffhanger about his death, or something that was unexpected or in doubt, this approach would have worked better. But I suppose it’s better than just starting at the beginning – that’s even more predictable.

What I’m trying to say is: there’s nothing innovative about the way this film is structured – and it works just fine. It uses still photos, family film clips, tv news footage, and interviews with important figures like Jimmy Carter, Rolling Stones editor Jann Wenner, Pat Buchanan, and many others. The fact is, this film is exactly what it claims to be: the story of the life and work of Hunter S. Thompson. Nothing more, and nothing less.

Cinematography: Most of the film is a compilation. This is a classic “archival film.” But there are plenty of interviews, which are shot unremarkably in mostly natural light in the offices of the people being interviewed. But they get the job done nicely.

Editing: Editing was the big job on this film. How to pull all that archival footage together to tell a cohesive story? That’s the trick. And it’s done very well in this film. But without discernible innovation. One memorable edit: Thompson shoots his typewriter – which functions as a metaphor for him shooting himself. Great way to handle it.

Sound and Audio: There’s one really fun bit of audio accident that made it into the film: At one point during an interview with Pat Buchanan, an extremely loud Harley motorcycle blasts off outside the window where the interview is taking place. Buchanan pauses, laughs, and says “I think that’s perfectly fitting, isn’t it.” Music is all period songs from the likes of Lou Reed, James Brown, and Bob Dylan. Must have been a hefty price tag on getting all those clearances.