OK I’m fully a third of the way into screening 100 docs. And one thing is clear: I’m most captivated by the small filmmaker teams, the people who manage to make film after film with just a couple of people. People like Werner Herzog, Marshall Curry, or Ross McElwee. Nick Broomfield and Joan Churchill are two filmmakers who have a long history of collaboration, with Nick often in front of the camera, which is run by Joan. But Broomfield is most known for being an early adopter of the “self-reflixive” style that would later be adopted with overwhelming box-office success by Michael Moore. For Broomfield, how the picture was made is part of making it, and he explains his thinking, questions, and includes the bits where he was wrong, which is part of the appeal.

OK I’m fully a third of the way into screening 100 docs. And one thing is clear: I’m most captivated by the small filmmaker teams, the people who manage to make film after film with just a couple of people. People like Werner Herzog, Marshall Curry, or Ross McElwee. Nick Broomfield and Joan Churchill are two filmmakers who have a long history of collaboration, with Nick often in front of the camera, which is run by Joan. But Broomfield is most known for being an early adopter of the “self-reflixive” style that would later be adopted with overwhelming box-office success by Michael Moore. For Broomfield, how the picture was made is part of making it, and he explains his thinking, questions, and includes the bits where he was wrong, which is part of the appeal.

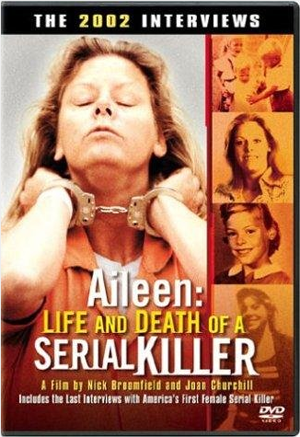

Synopsis: In 1992, Broomfield and Churchill made a film about death-row inmate Aileen Wuornos, who was convicted of killing 6 men. In that film, she claimed she had killed in self-defense to avoid being raped. Broomfield picks up the story years later in this 2003 film, as Wuornos date with the death chamber looms, and makes some discoveries that call into question both his previous beliefs about Wuornos, call into question her sanity, and the fairness of the legal system.

Story Structure: Broomfield approaches his films the way an investigative reporter might approach a story – he patiently visits the people involved, gets them on camera filling in details, then he follows the trail wherever it takes him next. Along the way, he shares his thoughts, questions his earlier beliefs, and generally takes you along on the filmmaking experience, so that you are (often quite literally) looking over his shoulder the whole way. Broomfield actually takes the witness stand in the trial at one point, putting himself squarely in the middle of his film in a style that has been called Les Nouvelles Egotistes. Underlying the personal approach is roughly chronological storytelling – the film opens with him catching you up to speed on the details of the story, his own involvement with it, and ends with the execution of Wuornos.

Cinematography: Joan Churchill operates the camera, in a cinema verite style that is unremarkable but remarkably effective. She catches Broomfield putting mic on, has the camera rolling when prison guards ask if they have any hidden cameras as they enter the prison (to which Broomfield, without missing a beat, says “just that rather large one there.”)

Editing: One thing I noticed in this film, which made it feel more like TV journalism than film, was that names were occasionally beeped out and faces obscured.

Sound and Music: There was some fairly bad audio in the film, like planes flying over during interviews and such. Again, this all combines to make the film feel like a piece of TV journalism, rather than a “film.” As the film ended, we hear a song that Wuornos requested be played at her wake. As it was being played, the camera follows one of Wuornos friends to her home in Michigan. It seems obvious that the next scene will be the wake itself, with the actual audio. But it’s not. The film just ends. Which felt like a missed opportunity to me.

I’m seriously intrigued by this approach to storytelling. I don’t think I have the presence or desire to be “on” all the time while making a film, but I’m fascinated enough that I’d like to try it on a short film just to see what happens. There’s something magical about inviting people to share your thoughts while making a film the way Broomfield does. But this early in my career, my thoughts aren’t very coherent, so I’m not sure they’d be worth sharing. Yet.