In continued honor of editor Karen Schmeer, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver last weekend in New York, last night I screened The Fog of War, the most acclaimed film she worked on. I was surprised to see that she was one of three editors listed in the film, which is directed and produced by Errol Morris. Which leaves me curious why Morris uses more than one editor on many of his films. I did a little Googling and found an interview in which Morris explains how he went through half a dozen editors on this first film before he could find someone who could make a film out of his footage. Fog of War, though, began as TV series he ran briefly, called First Person, in which Morris interviewed interesting people for 30-minute episodes. He had the idea of inviting Robert McNamara, and the 30 minute interview was so good, that he knew it had to become a film.

In continued honor of editor Karen Schmeer, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver last weekend in New York, last night I screened The Fog of War, the most acclaimed film she worked on. I was surprised to see that she was one of three editors listed in the film, which is directed and produced by Errol Morris. Which leaves me curious why Morris uses more than one editor on many of his films. I did a little Googling and found an interview in which Morris explains how he went through half a dozen editors on this first film before he could find someone who could make a film out of his footage. Fog of War, though, began as TV series he ran briefly, called First Person, in which Morris interviewed interesting people for 30-minute episodes. He had the idea of inviting Robert McNamara, and the 30 minute interview was so good, that he knew it had to become a film.

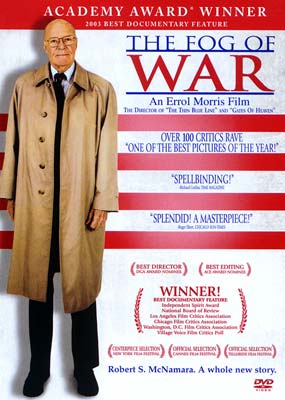

Synopsis: Former Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, widely regarded and reviled as the architect of policy that resulted in the Vietnam War, recounts the story of his life and muses on the lessons he’s learned about the limits of power.

Story Structure: The film is interview-driven, and structured around 11 lessons from McNamara’s life, which serve like chapters in a book to break the film into distinct parts, which loosely follow a chronology of his life. The classic elements of Morris filmmaking are all here: Penetrating eye contact with the interview subject, supported by news footage, historical photos, and occasionally the voice of Morris asking questions.

Cinematography: Memorable shooting/editing technique: This is the first time I’ve ever seen a sequence played in show motion, with fast-motion layer running over it simultaneously. The result is a dreamy state, a pause in the pace to reflect on the words that are being said, a disassociation with reality, stepping into another world. It’s a device used repeatedly throughout the film, and it’s killer. It was used when someone is flipping through pages of an open book, and also to show people walking down a street. He uses it again to show the Vietnam Memorial – with people lingering in slow motion while people rush past at a fainter percentage of visibility. It’s a beautiful technique that I’m totally going to borrow and build on in my own work.

There’s a memorable scene which plays forwards and later in the film backwards, which shows dominoes falling across a map of the world. This is of course a reference to communism taking over the globe, the rationale for getting deeper involved in Vietnam. It’s shot at a high frame rate, and played in silky slow motion. The b-roll of tape recorders (with shallow depth of field) is also shot in slow motion, looks really beautiful, and works against the tape recordings it’s paired with.

The film is wrapped up with a series of shots of McNamara driving in his car through rain-soaked streets. It’s beautifully shot: close up on his glasses reflecting trees passing by, but with his eyeball huge; top of his head and rain-dropped window above. It reminded me a little of the driving scenes of Al Gore in Inconvenient Truth, only Gore as a passenger in those. The fact that McNama is driving himself seems to portray how his time and come and passed.

Editing: What’s different about this film from most Morris films, and mildly disconcerting, is the amount of jump cutting. I’m pretty sure it was included for a reason: to show how difficult it was to get McNamara to answer in complete sentences, and to show how much he attempted to steer the conversation.

An interesting editing technique (which might more probably be called an animation or special effect technique) was a shot in which the camera floats down a column of falling bombs (animated, presumably, but begins with a still B&W photo and it’s like we can travel into the photo, and down among the bombs, which drift past us as we continue down into them. It’s way more powerful than the typical zoom and pan on photographs for it’s impact to draw you in.

Playing things backwards is also a recurring device used in this film to show that things we thought happened actually didn’t. For example, the torpedo boats that supposedly attacked US warships in Vietnam, and were the inciting incident for massive bombing by the US, in fact never happened.

The film ends with a powerful line delivered by McNamara, who is quoting TS Elliot:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

Music and Sound: Philip Glass again provides the soundtrack for the entire film, as he does on previous films like Thin Blue Line. My main critique is that if you’ve heard one Glass soundtrack, you’ve heard them all. The music is almost invisible to me in the film, and maybe that’s why Morris keeps returning to this composer, to keep the attention on the subjects with as much force as his Interrotron.