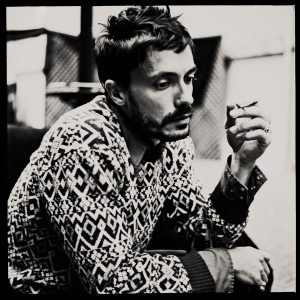

As Vincent Moon walks into the small theater at Northwest Film Forum, he looks nervous. About a dozen fans and local filmmakers have signed up for a 3-hour workshop with this frail-looking Frenchman, and I’m one of them. Between bagel bites and coffee sips, he begins rambling about his disdain for film school (even though he taught at one recently and even attended one for a few years himself). After he drops the third or fourth name of a director I’ve never heard of, I begin to wonder whether the class was worth my time.

As Vincent Moon walks into the small theater at Northwest Film Forum, he looks nervous. About a dozen fans and local filmmakers have signed up for a 3-hour workshop with this frail-looking Frenchman, and I’m one of them. Between bagel bites and coffee sips, he begins rambling about his disdain for film school (even though he taught at one recently and even attended one for a few years himself). After he drops the third or fourth name of a director I’ve never heard of, I begin to wonder whether the class was worth my time.

Then he shows this film. It’s short, under 10 minutes. Much of it is blurry and out of focus, and the jittery handheld camera work screams “amateur.” But I begin to pay closer attention as I see that the film was made in a single take. Climbing into the back of a pickup truck with a group of musicians in Argentina, Moon had filmed handheld as they drove through the streets. That’s right, shooting handheld from a vehicle, zooming in for tight shots of faces, disdaining the most basic rules of photography (keep the camera steady; keep the subject in focus, etc). Crazy!

But his camera is definitely on an intelligent quest. It reacts to what it discovers spontaneously. When the camera catches a blur of a couple looking up as the truck passes, it follows them until they disappear, then lifts to peer up at the anonymous windows rushing by, before returning in an arc to the musicians. A parked police car slides by, sun glints off the singer’s dark glasses, and he zooms into them as they drive into a dark street. The scene fades naturally to black, and I realize I’m on the verge of tears. Huh? How did THAT happen? Who is this guy?

Apparently the coffee is working, because Moon is looking a lot more comfortable now, and smiling. “What you think of dat one?” he says, in his heavy French accent. “Zat OK?” A kid with a DSLR camera over his shoulder raises his hand and says, “I want to know everything: what kind of camera did you use, how exactly were you holding it, what your settings were on the camera, what software did you use for color correcting, everything.” Moon laughs politely and wiggles away from the question by pointing out that his work is really an effort to get away from the technical tyranny that pervades so much of filmmaking. In fact, it was the simplicity of still photography that at first lured him into making pictures.

If there’s one thing I’ve come to understand and resent about filmmaking, it’s that making almost anything worth making seems to require conceiving, funding, building, and commanding a small army. The biggest difference between making a film and making a photograph is that the the former is proactive, and the latter is reactive. Filmmakers are always planning and collaborating and organizing, while photographers dance with the moment. It’s a critical difference.

Moon set out to make films the way a photographer takes pictures: often in a single take, often with just himself, sans crew. “I never know what I’m going to do,” he says. “I can adapt myself because I don’t have a plan.” His method: travel to some exotic location for two weeks. Spend the first week hanging out in bars talking to locals and figuring out who the best local musicians are; spend the second week meeting them and filming them; and you’re done.

Well note quite done. The heaviest work for most indie filmmakers isn’t making the film – it’s finding an audience. But Moon shrugs that part off. “I don’t care about people watching. I care about people making [films].” The 20th Century, he explains, was characterized by a separation from artists and society that reached it’s peak in the massive success of bands like The Beatles. You were either in the band (cashing the checks), or in the audience (buying the records). But with the rise of Internet comes the rise of the amateur. Incredibly talented artists can increasingly be found everywhere, doing it for the love of doing it. And he sees his own work as part of that trend. “I make films for the small screen,” he says. But in a world with more than 40 million iPhones, does size matter in the same way it used to?

But most photographers and filmmakers I know apparently haven’t gotten the memo about the death of the audience. They still care passionately about building the largest audience possible on the biggest screen available. And they definitely want to get paid for their work. Moon, in stark contrast, posts most of his work to the internet under a Creative Commons license, which allows other artists to share, remix and reuse his work (provided they are not making money from it.)

So how does he make a living? Well, at least one major band, REM, has hired him to make a music video to the tune of $150,000. But Moon seems embarrassed to admit that, and says wasn’t his best work. In fact, Moon’s most steady form of income these days, he says, comes from speaking engagements like this one. Moon, it seems, is proceeding to make films from the sheer love of making films, following the same artistic impulse as his subjects, and believing the rest will work out somehow.

“I make films to remember,” he says.

Northwest Film Forum will be showing Vincent Moon’s films every evening at 8pm Saturday through Thursday.

Pingback: Miguel Gomes in Seattle tonight for NW Film Forum screening | Dan McComb

Please help Vincent Moon finish four films at ATP: http://kck.st/rdTIr8

Hi, thanks by the article, but the musician you are referring to its from Chile.

Thanks for the correction Domingo.