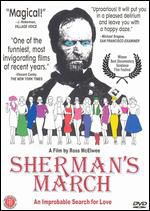

I love Sherman’s March. There’s so much to take away from this film, I hardly know where to start. So I’ll start at the beginning: with filmmaker Ross McElwee misdirecting me into thinking that this is really a film about Sherman’s scorched-earth march across the South near the end of the Civil War, complete with stentorian hired-voice narration while arrows depicting the march show us the route on a map. Psyche!

I love Sherman’s March. There’s so much to take away from this film, I hardly know where to start. So I’ll start at the beginning: with filmmaker Ross McElwee misdirecting me into thinking that this is really a film about Sherman’s scorched-earth march across the South near the end of the Civil War, complete with stentorian hired-voice narration while arrows depicting the march show us the route on a map. Psyche!

Cut to empty Manhattan flat, with McElwee narrating. His girlfriend, he tells us, has just dumped him, triggering an existential crises in his life. He’d just received $9,000 to make a film about Sherman’s March (a decent chunk of change in 1981, when he did the filming). McElwee resolves to make SOME kind of film as therapy, and we’re off on a nearly 3-hour ride that loosely follows Sherman’s march route through the South, but very closely follows McElwee’s quest to find a new girl.

This is an intensely personal film. In fact, I discovered there’s a special genre of documentary in which this film resides called, appropriately enough, “personal documentary.” The filmmaker adopts a “lovable loser” role describing with deadpan humor his luckless encounters with women, many of whom are past girlfriends whom he visits while on his trip through the south. A journey is a powerful metaphor, and so is the figure of William Tecumseh Sherman, with whom McElwee identifies as someone who was mostly ignored or despised during his own day.

What I admire about this film is the ability that McElwee showed to make his OWN film. The historical Sherman’s March simply provides a structural support for the film, the canvas if you will, on which the artist paints. I saw another film recently that attempted a similar approach: An American Journey, in which journalist-turned-filmmaker Philippe Séclier retraced the steps of photographer Robert Frank. However, Séclier doesn’t manage to make the journey his own anywhere near as convincingly as McElwee does. And that’s the takeaway for me from this film: to make really good films, they must be films that only you YOU could make.

Intriguingly, I don’t think this film would have worked had it purported to be a film about a guy going in search of a girlfriend in his native South. That’s too obvious. It needs the twist, it needs to misdirect us a little bit, in order for us to see it’s genius. Our minds crave seeing beyond the obvious.

Random observations: The filmmaker maintains a deadpan narrative delivery throughout, which is funny. The humor helps the film work. He also keeps the camera rolling through a lot of delicate conversations and first meetings, which must have required a lot of negotiation. He uses a simple convention three times during the film: a shot of the moon (in different phases for each of the scenes) with his voiceover describing his dreams. Very effective bridge technique between sequences. In a way the film is a celebration of Southern women. We really get a glimpse into their character.

I love how he enters the film saying “I have no idea what to film next.” You really almost feel sorry for him at that point, you identify with him. And you want to keep watching to find out what he DOES find to film.

Beautiful shot: when he finally gets the MG running, you know he’s got it running when you see the reflection of the car in the stainless steel gasoline tanker, which is a reveal shot – you have no idea what it is at first. He managed to shoot it while driving. Kids, don’t try this at home.

Ultimately he does get a nice cross section of southern life, everything from the nut jobs at the survivalist enclave, to the women’s rights activist who keeps going back to a boyfriend who appears to be no good for her.

Tip: If you screw up and forget to record sound, as McElwee did on two occasions in the film, just admit it and narrate over the visuals! This technique allowed him to cover his mistakes and helps build the case that he’s a lovable loser.

He films himself walking around the battlefields looking a little lost. Nice bridge scenes. Also a sweet camera move when he films the big plastic rhinoceros, in which he starts out walking backwards in front of the guys who are carrying the rhino, then stands to one side and lets it pass away and travel into the scene. Simple camera move but nice one that tells story and is nice to look at.

He provokes a confrontation scene by following Burt Reynolds into the place where he’s making a film. Reynold’s henchmen see him right away and he films them for a few seconds while they confront him, which cuts straight to a police officer writing down his name. Yes, he keeps the camera rolling. Remember that.

I was really curious how he’d end this film. Does he find a girl? He finds a way to tie it together that feels honest and hopeful.

This film was full of lessons for me. And it turns out that McElwee went on to become a professor at Harvard University, where he teaches – surprise – filmmaking.