I love my 5dmkiii. There’s still nothing like shooting video on a full-frame sensor. So when Magic Lantern released a firmware hack that allows shooting video in raw, I was eager to try it out. And it’s amazing: super vibrant 14-bit color, captured with 12.5 stops of dynamic range. That’s a whole ‘nother league beyond the 8 stops of DR and 8-bit color that comes out of the 5dmkiii natively. But it’s quirky to shoot with, and buggy enough that I haven’t been able to use to complete a project. Until today.

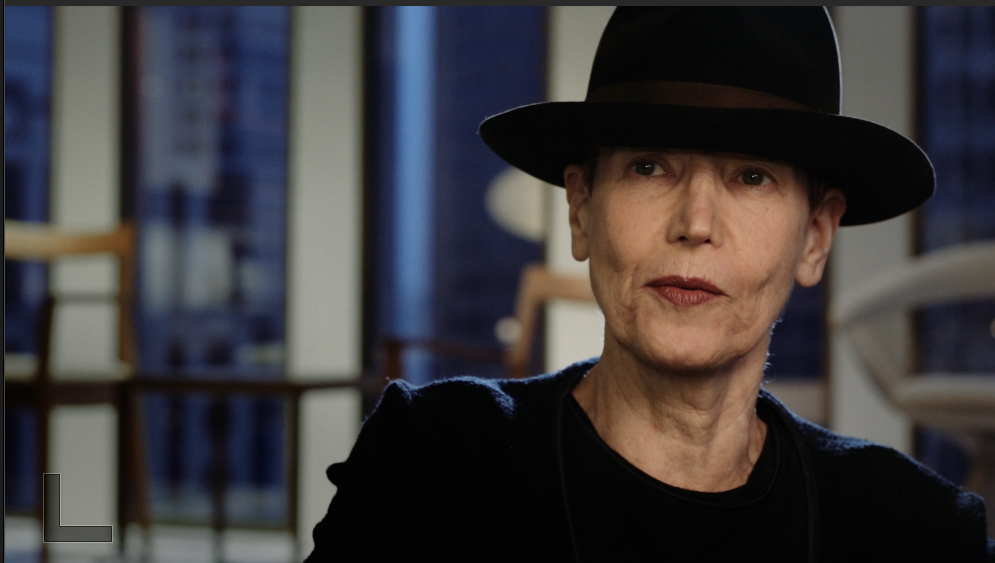

Today Lisa and I are thrilled to release our first project shot entirely in Magic Lantern raw, The Dollmaker. It’s part of our Makers series, which focuses on people who make things by hand. We love topics that are slightly dark, and when we saw Clarissa Callesen’s work, we knew we had to film her. She graciously allowed us to invade her studio for a day, and shoot this piece.

Most of the credit for this piece goes to my partner Lisa Cooper, who produced, directed and edIted the film. I stayed focused on cinematography on this one. And I have a few things to say about shooting raw on the 5dmkiii.

First, it’s a data hog. A 64 gigabyte CF card fills up in about 10 minutes. And the cards are expensive enough that I only own three of them. So it was necessary to lay off the cards as soon as they were shot, in order to always have a fresh one ready to go. This would work better if we had a DIT person on set, but of course, that’s a luxury we don’t have (or want, really) for these unpaid, self-assigned projects. It basically meant that we had to have a laptop with CF card reader and hard drive going all day on location. But when you consider that old film spools were about 9 minutes, hey, it’s not so bad.

First, it’s a data hog. A 64 gigabyte CF card fills up in about 10 minutes. And the cards are expensive enough that I only own three of them. So it was necessary to lay off the cards as soon as they were shot, in order to always have a fresh one ready to go. This would work better if we had a DIT person on set, but of course, that’s a luxury we don’t have (or want, really) for these unpaid, self-assigned projects. It basically meant that we had to have a laptop with CF card reader and hard drive going all day on location. But when you consider that old film spools were about 9 minutes, hey, it’s not so bad.

Second, there is quite a bit of assembly required in post, before you get a video clip. I had to unpack the files using a utility called RawMagic, and then I had to convert the many individual DNG files (one for every frame of video, which each weigh about 4 megabytes) into ProRes for editing in Final Cut Pro X. I used Adobe After Effects for this, and it’s mind-numbingly slow. Davinci Resolve has since added support for the type of Cinema DNG file that Magic Lantern produces, and this speeds up the process tremendously. Best of all, the Lite version of Resolve is free, and nearly full-featured.

Third, once you get a ProRes daily generated, the colors, crispness and dynamic range of the image are freakishly awesome. We love the ProRes file so much that we just throw away the raw. It’s too expensive for us to store it, and the ProRes is so good, in comparison to what we’re used to with H264, that we are thrilled with it. But this does mean you have to be making some basic color grading decisions at the time you generate the daily. Not a big deal – because with a DSLR, you are making those decisions at the time you shoot anyway. Saving the raw files would allow you to defer those choices as long as you wanted.

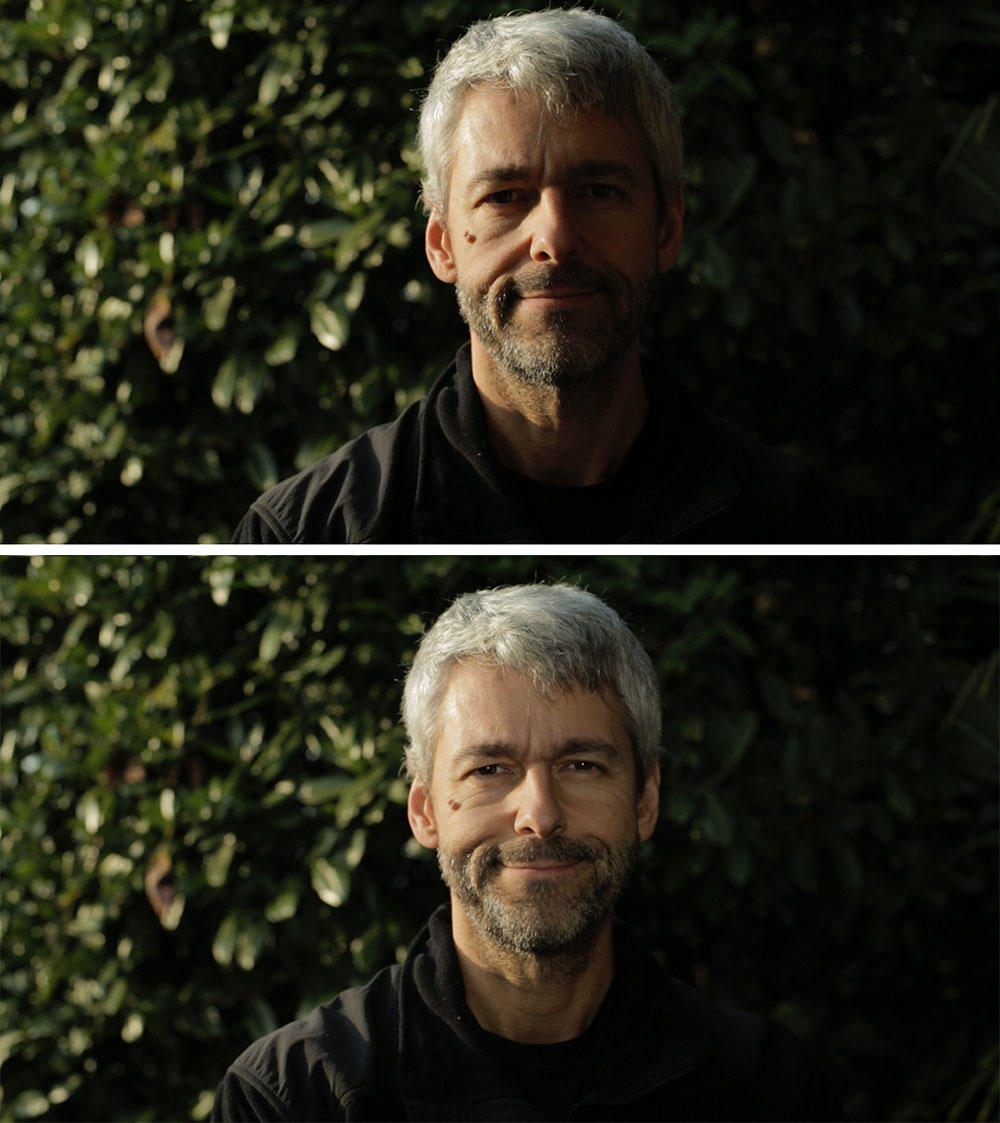

Fourth, raw wants slight overexposure, unlike h264 on the 5d, which wants slight underexposure. I’m still getting used to this idea. But with Magic Lantern raw, underexposure = noise. Lots of noise. You can add denoising in post, and the 10-bit daily cleans up nicely, much nicer than the 8-bit I’m used to. But still, you’re so much better off to overexpose a little, and not have to deal with the noise at all. I’m finding about 1/2-stop of overexposure is about right. It’s kind of like shooting negative film – a little overexposure just gives you more detail to pull a print from.

Fifth, there is no sync sound in Magic Lantern raw. So that means clapping everything, which I kind of hate doing on docs. I prefer using PluralEyes to sync my footage. And you can’t do that with Magic Lantern raw. You’ll notice this video has no sync sound – we recorded the sound effects that you hear, but I had to play around with getting them to sound right, since they weren’t synced. Another big time drain. So I definitely would not recommend using Magic Lantern raw on any project that needed sync sound.

Sixth, color grading is harder, even though the file is better. It’s the paradox of choice: you can do so many things in the grade, that you can get lost in the weeds trying on options. Because I’m not a professional colorist, I like the predictability of dropping FilmConvert Pro onto my footage, which is pre-mapped to 5dmkiii with the picture style that I use. I get great results every time that way. But with these raw files, you have to really approach the grade like a pro, without presets. So it’s more work.

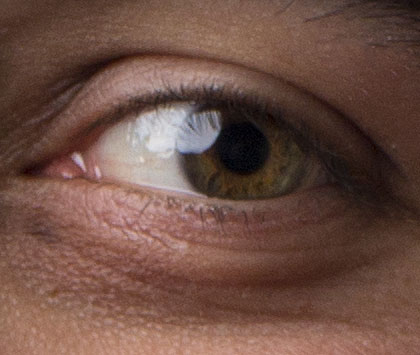

Seventh, you can turn any lens into a macro by using Magic Lantern’s crop-sensor shooting mode. But beware: if you have an hdmi monitor connected, it will result in pink-frame tearing. In fact, you’ll get a few random pink frames into your footage even if you disconnect the monitor. So it’s not a feature you can really depend on. But there’s something incredible about being able to be shooting with a 50mm lens, and just punch in the focus, and start rolling at 150mm equivalent, up close. Notice the shot of the brooch in the heart-shaped case at 1:22:20. You could pull the artist’s fingerprint off one of these frames! That’s with a 50mm, non-macro lens, in crop-sensor mode. It’s sick.

I’ll definitely be using Magic Lantern more in future projects. The image is just too good to be resisted! But the challenges associated with acquiring it and the workflow issues will probably keep me from using this extensively for now.