After watching another Herzog film, I’m struck by how clear it is that Herzog makes films about topics that not only interest him, but somehow ARE him. Dieter Dengler, the German-born Navy airman whose epic escape from behind enemy lines is the subject of this film, is the Herzog character in this film. In fact, it’s the only Herzog film I’ve seen in which Herzog allows the narration to switch seamlessly between Dengler and himself, and it’s momentarily disorienting because you’re not sure whose German accent you’re listening to.

After watching another Herzog film, I’m struck by how clear it is that Herzog makes films about topics that not only interest him, but somehow ARE him. Dieter Dengler, the German-born Navy airman whose epic escape from behind enemy lines is the subject of this film, is the Herzog character in this film. In fact, it’s the only Herzog film I’ve seen in which Herzog allows the narration to switch seamlessly between Dengler and himself, and it’s momentarily disorienting because you’re not sure whose German accent you’re listening to.

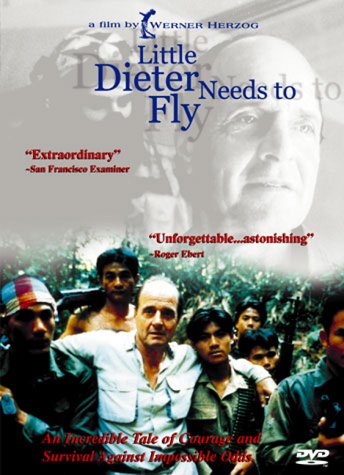

Synopsis: During the Vietnam War, Dieter Dengler was shot down behind enemy lines, and this documentary recounts the story of his imprisonment and ultimate miraculous escape and rescue. Much of the film was made during a trip to Vietnam in which Herzog accompanied Dengler to the locations where key events happened, where he hired actors to partially recreate events. Dengler narrates most of the film, telling his own story with a deftness and sureness that is nothing short of extraordinary. No wonder Herzog later made a narrative feature film based on Dengler’s life after he died in 2001. It’s pure, unvarnished heroism, and anyone who watches the film is likely to be as captivated by Dengler as Herzog clearly was.

Story and Structure: The film opens with a Bible quote from the book of Revelations, then unfolds through 4 named acts: The Man, His Dream, Punishment, and Redemption. Herzog goes deep in the filmmaker’s tool kit on this one, using archival footage, military training film footage, recreations with actors filmed during a return visit to Vietnam, accompanied with his own narration, to tell the story. But mostly, the story depends on Dengler’s own words, which at times are so matter-of-fact in describing unspeakable horrors that it’s surreal.

Cinematography: The last scene in the main part of the film is very powerful (but something tells me, given the situation, could have been even stronger). It begins with Dengler walking through the massive military aircraft graveyard at Davis Monthan Airforce Base near Tucson. Next we’re seeing him walk from an aerial shot, in which we leave him behind and pass row after row of decommissioned Vietnam-era planes. It’s a landscape of dreams, in a place where Dengler could sleep forever, and a fitting end to the film, as those willing to sit through the brief credits soon discover in the postscript, filmed at Arlington National Cemetery.

The film contains a scene early on that has become legendary in documentary filmmaking circles, in which Dengler arrives at his home and tries all the doors, opening and closing them, explaining that it’s a habit he’s gotten into since his escape to ensure that he can leave whenever he likes. Only, that piece of the story was one of Herzog’s moments of “ecstatic truth” shot not because it was real, but because it showed what it really felt like to be Dengler. And as long as Herzog is forthcoming and honest about his use of such techniques, which he has always been, I support his use of such fabrication. After all, all cinema is manipulation, and filmmakers are not, thank God, journalists.

Editing: Much is woven together in this film: family stills, interviews, news footage, dramatic recreations. And it all hangs – but without anything rising to the level of memorable editing, in my view. It just works, in a solid, journeyman, well-crafted kind of way.

Music and Sound: Herzog’s music tends to be symphonic, operatic, and epic, and this film is no exception. There’s even some Tibetan throat singers, also a recurring theme in Herzog films. This is where I find myself slightly critical of the film, on the one hand acknowledging the fact that his choices are definitely moving, while on the other wondering whether there might have been another way, perhaps a more original way.