Back in the old days, filmmakers had to clap wooden sticks together to match sound and picture. Then, editors had to meticulously nudge the two together before they could go to work on more creative tasks.

There may still be good reasons for slating your takes, but syncing footage is no longer one of them. With PluralEyes, an application included in Red Giant’s Shooter Suite, all you have to do is record reference audio on your camera, and let software do the rest.

But before I get too far along, let me be clear that what I’m talking about here is dual-system sound. This is sound recorded the right way: by a sound recordist. Someone whose job it is to make your production sound awesome. Many beginning filmmakers think they can cheat and just stick a shotgun mic on top of their camera, and call it good. You can’t. Ninety percent of success in recording dialog depends on getting the mic close. Really close. About 6 inches, in a perfect world. And you wouldn’t want to limit your shot list to 6 inches from your talent, would you?

There are other ways to keep your audio and video in sync, such as using genlock to match the timecode between recorder and camera. But the complexity, not to mention the cost of cameras and recorders that support this method, puts this solution beyond the reach of many smaller filmmakers.

But, if you’re a small filmmaker, why shell out the $199 for PluralEyes to sync audio and video? Isn’t this capability built into Final Cut Pro X? Yes, but FCPX only syncs one clip at a time. That means you have to tell it which clip goes with which audio, and then press the sync command for every clip. If you’ve been shooting all day, this starts to look a lot like syncing the old fashioned way: tedious. PluralEyes lets you batch sync all of your clips at once.

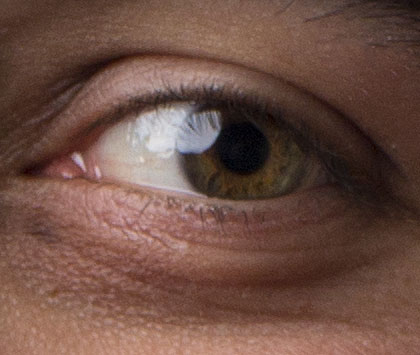

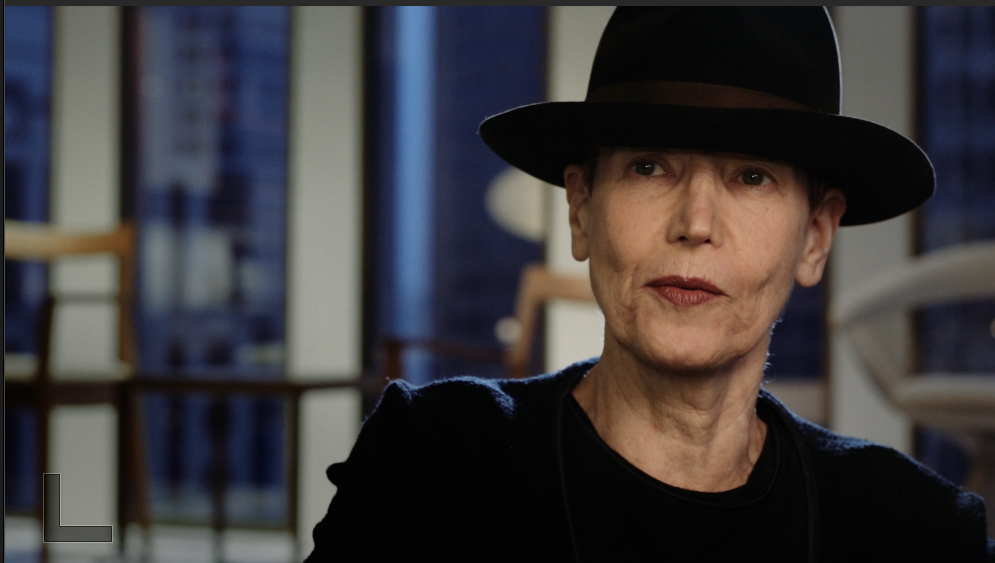

OK, let’s dive in. I’m going to show you how I synced footage on a multi-cam shoot I did to produce this profile video:

My camera assistant shot with a second camera. The subject, a video blogger, also contributed footage that he was shooting himself, for three cameras total. Each camera was recording audio (which I’ll refer to as reference audio, or a reference track.) The high-quality audio was recorded separately with a Tram TR-50 lav mic clipped to the talent, recorded onto a Zoom H4N via a Sound Devices MixPre.

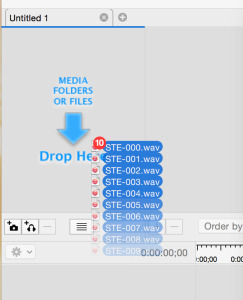

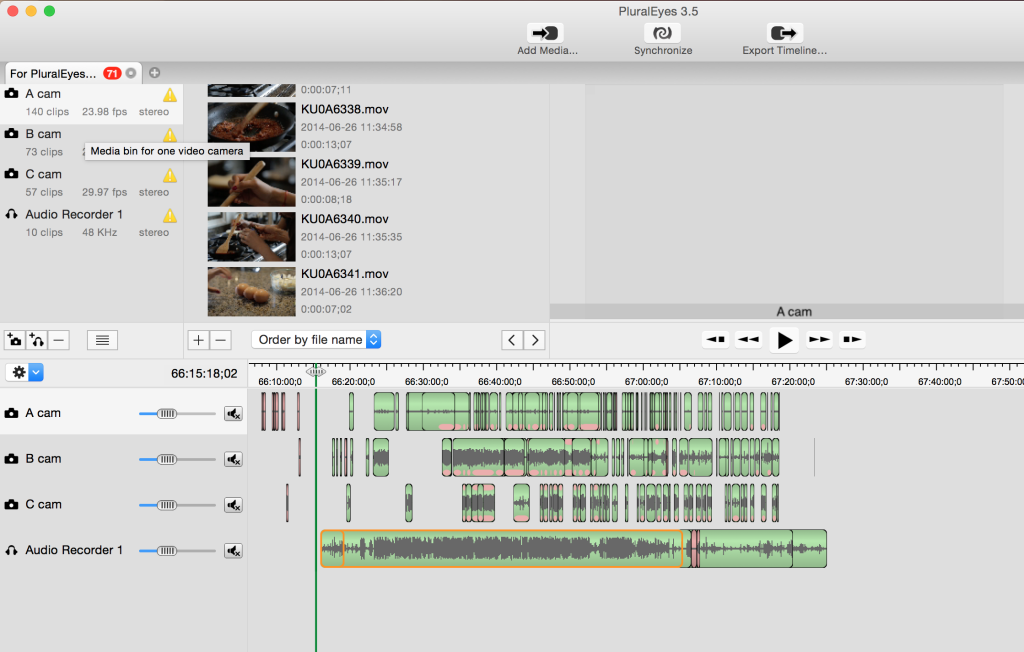

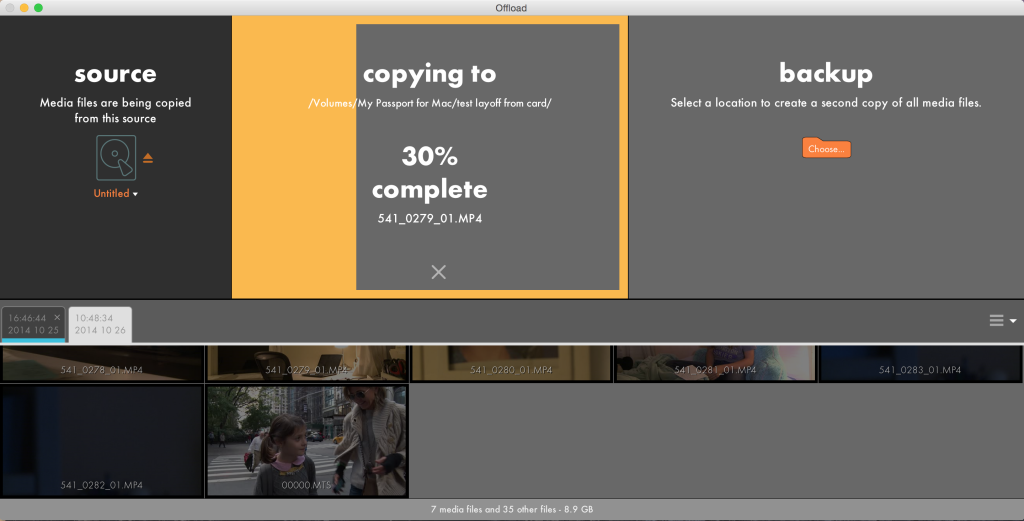

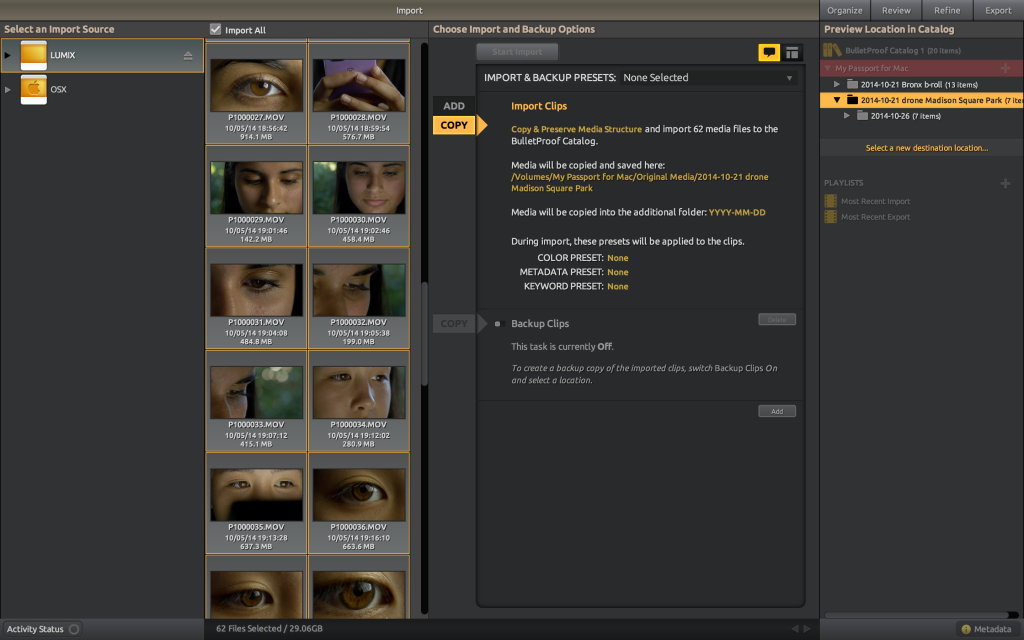

To get started, drag all of the audio files into PluralEyes target window (you can drag them all at once or one at a time). Then drag the video files in. PluralEyes is smart enough to figure out which files are audio files, and which are video files. It will also attempt to figure out whether the video files you’re dragging in are from different cameras. This can take quite awhile.

I’ve observed that PluralEyes can get confused if you drag all of the video files in at once. Try dragging one camera at a time into the window, and wait for it to finish processing, before dragging in the next one.

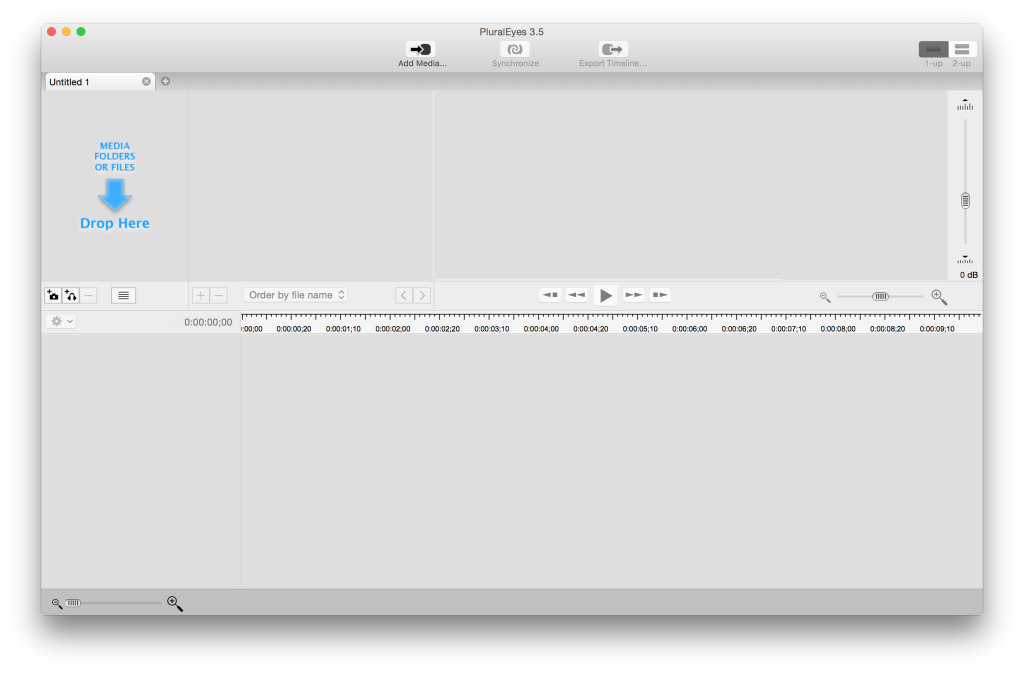

Once you’ve loaded all the files, you should see that PluralEyes has organized each camera’s footage onto its own track, and audio as well, like so:

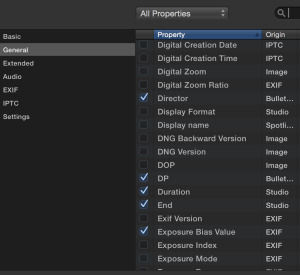

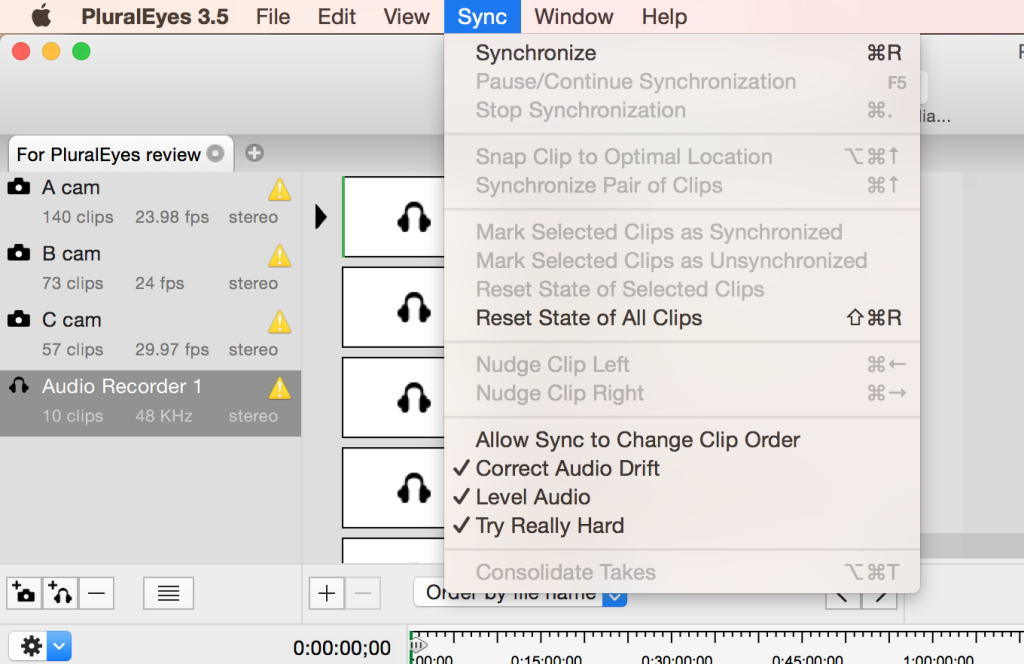

So now we’re all ready to sync our footage. But first, let’s take a look at the sync options:

Allow Sync to Change Clip Order. I recommend leaving this one off. Most of the time, your audio clips and video clips are recorded sequentially. So you WANT them in order. The only time I can think of that you’d want to turn this off is if you have named your audio or video files something other than sequential numbers prior to sync.

Correct Audio Drift. This is a killer feature, so be sure it’s turned on. If for some reason your recorder audio doesn’t match the reference audio throughout the duration of the clip, this will fix it by very subtly stretching or shrinking the length of the file so that it lines up.

Level Audio. Sometimes the audio on your reference track will be too low for a good match. Checking this box will raise the levels on your reference track so that it can work with it. Red Giant suggests leaving this one turned off by default, and only using it if you have trouble getting files to sync. But I figure why not start where you’re going to end up? So I leave it on all the time.

Try Really Hard. Of course you want your software to do that, right? Leave it on. It will slow down the time it takes to sync, but do the best job possible.

Now click the Synchronize button at the top middle of the screen. Then sit back and watch your footage move into sync with the audio automagically. When it’s done, you should see something like this:

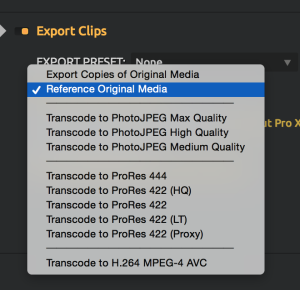

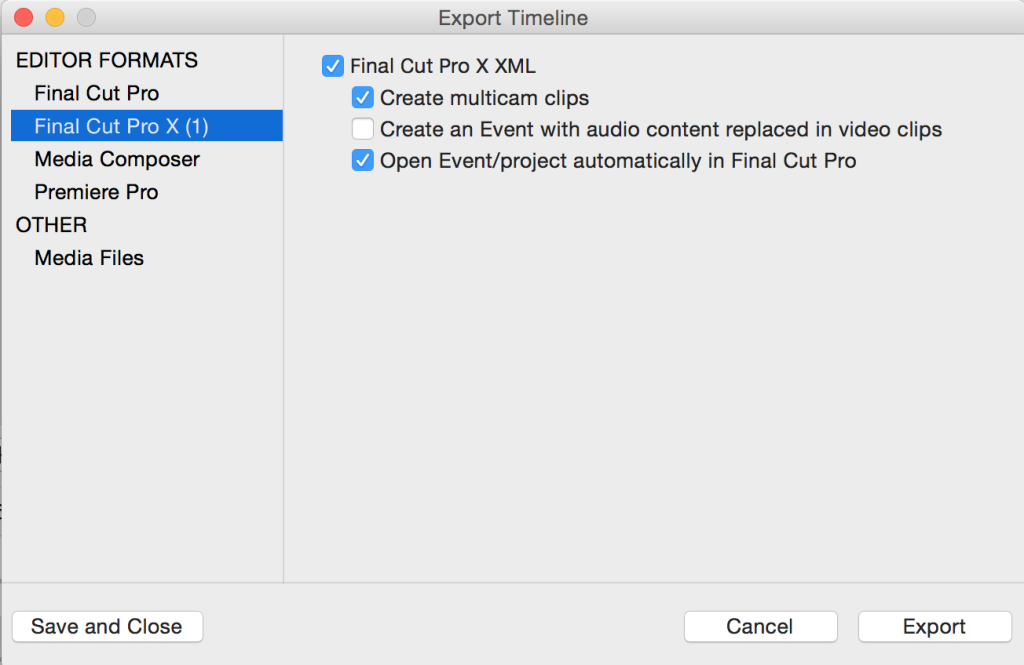

Things are lined up, and now it’s time to export. Click the Export Timeline button, and you’ll get the option to choose your editing format:

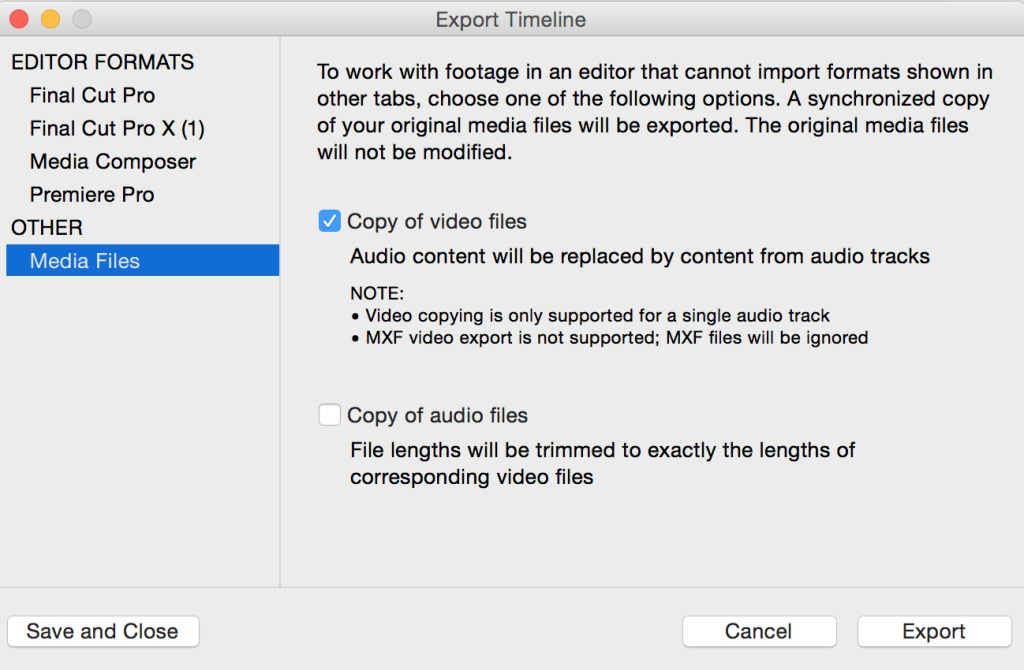

Supported NLEs are Final Cut Pro 7, Final Cut Pro X, Avid, and Premiere. But here’s a power tip: the Other option allows you to create new clips, with the good audio replacing the bad. If you start your project by importing these clips only, and ignoring the reference clips, every clip in your project will be a “good” clip and you won’t have any issues keeping track of which is which.

I’ve found this is a good choice when shooting with a single camera, and you know you only want to use the sync audio and ignore the rest (as with an interview, for example).

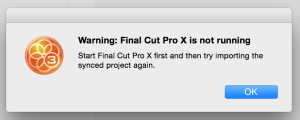

If you choose the option to Open Event/Project automatically, and FCPX is not running during the export, you’ll see this error:

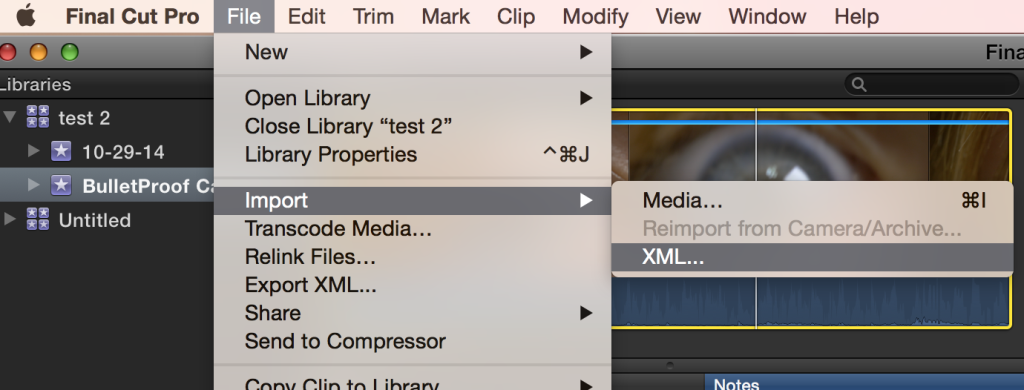

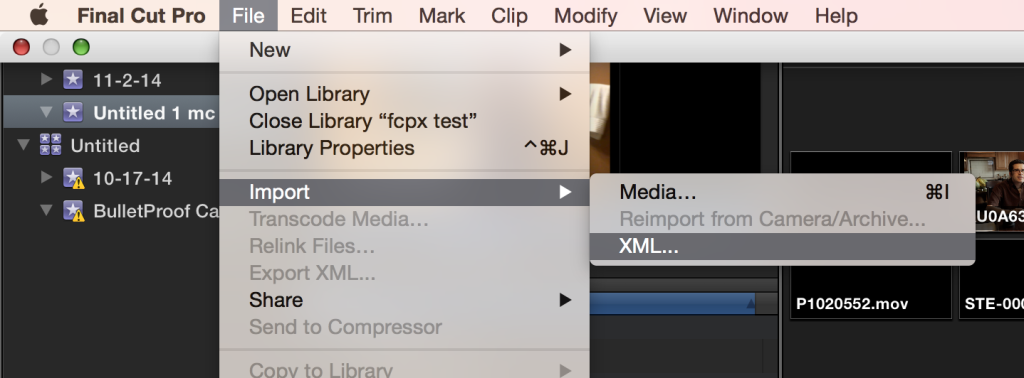

If this happens, it means the file won’t be imported automatically. No problem, you can do it manually. Open FCPX, and go to File > Import XLM.

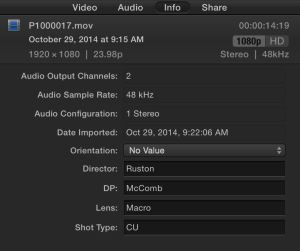

This will create an event which contains your exported files.

Sometimes PluralEyes gets confused. If you are attempting to sync the same footage repeatedly, it’s a good idea to throw away the temporary files that PluralEyes creates. Look inside the directories containing the audio and video files, and throw away the folders called PluralEyes Synctemp.

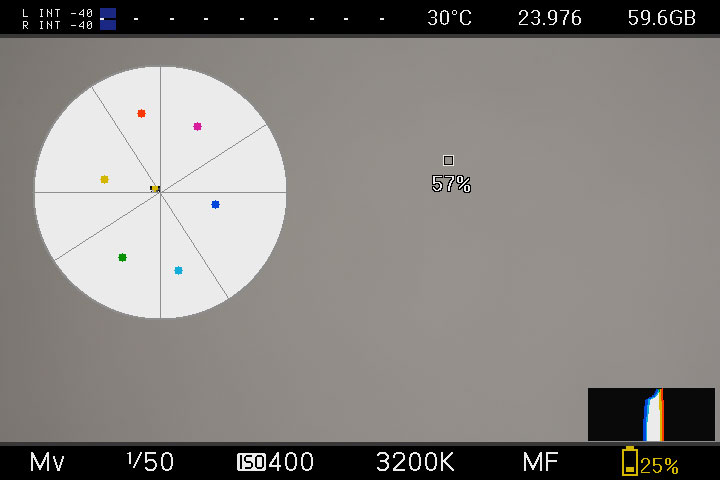

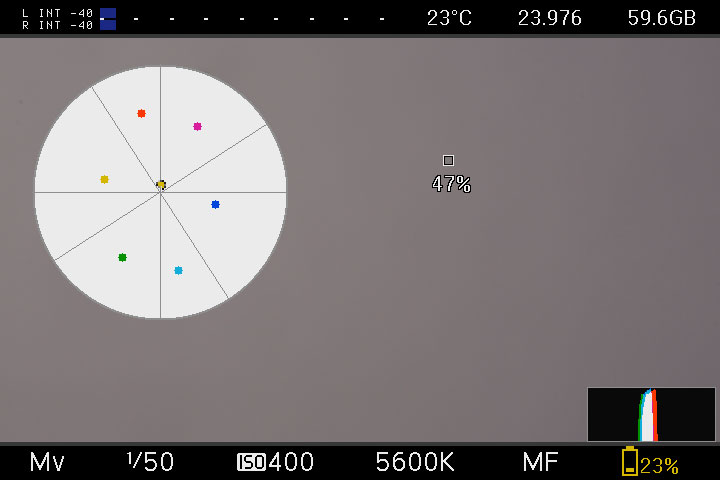

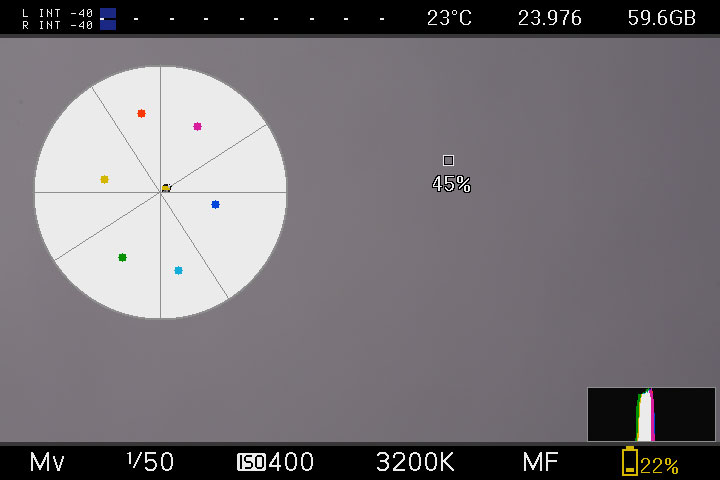

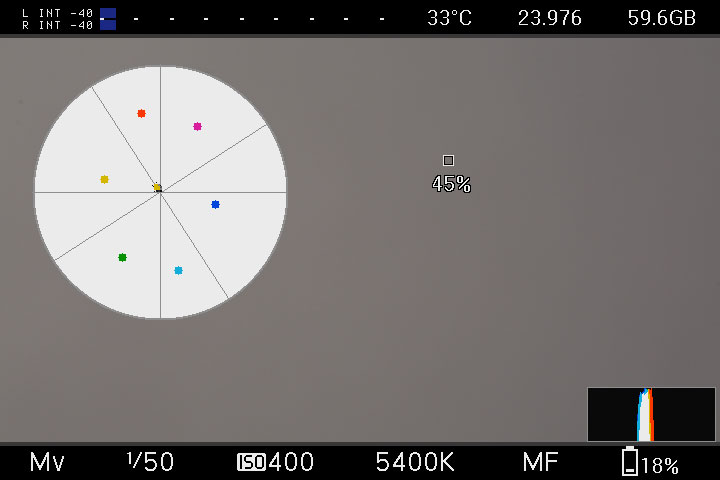

What if you have video clips that are recorded at different frame rates? Will that cause sync issues? Sometimes, but if that happens, try again. In the project used for this post, the three cameras were all shooting different frame rates: 23.976, 24, and 29.976. On the first sync attempt, it came out scrambled. So I tried again after throwing away the temp files, this time adding each camera one at a time instead of dragging them all in at once. The second time, everything synced fine.

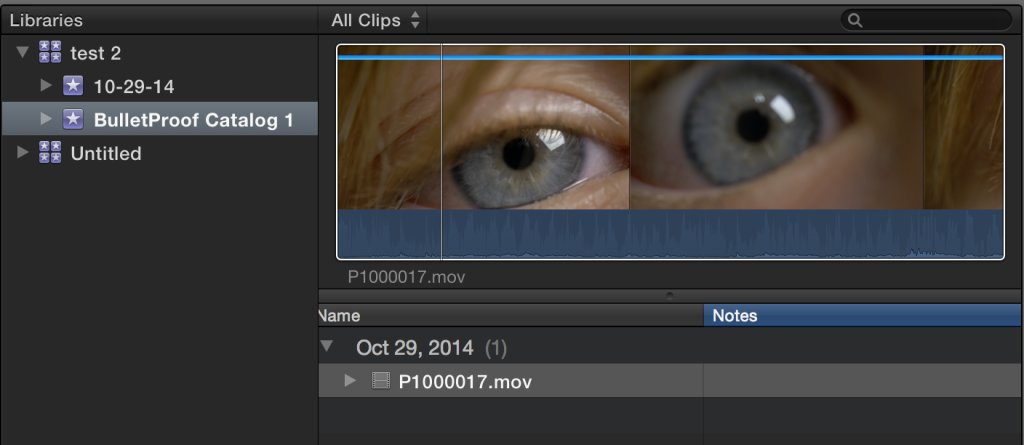

Here’s how the multicam clip looked after importing correctly:

Notice the audio files starts with 000, and count up sequentially as you go from left to right in the timeline. That’s what you want – file names in order. Notice that the audio file names include “drift corrected,” which means PluralEyes had to do a little work to make them match exactly.

PluralEyes has earned a place at the heart of my workflow, freeing me of the tedium of slating and the complexity of genlock. If you hear the sound of clapping on my sets, it’s because someone is happy.

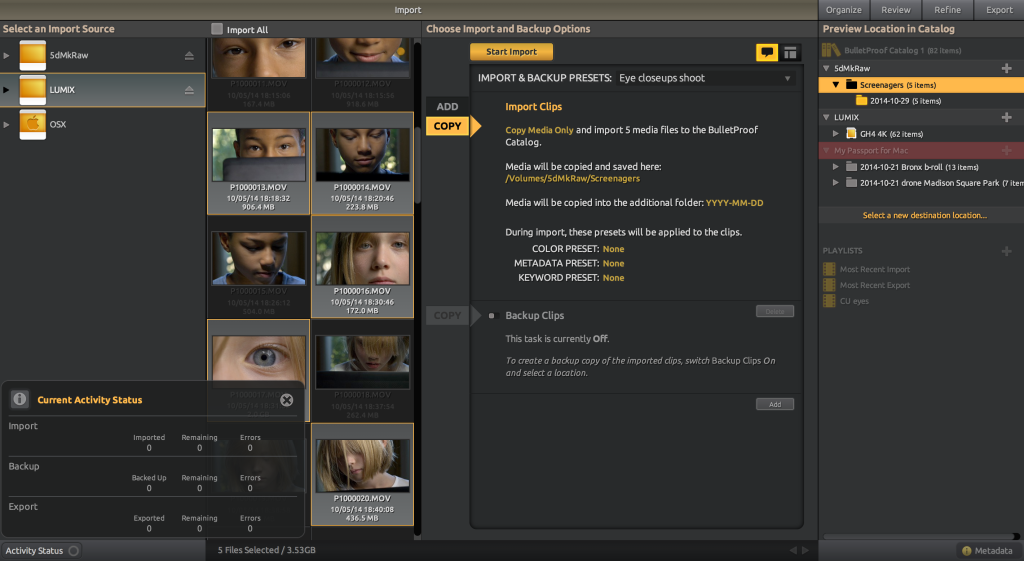

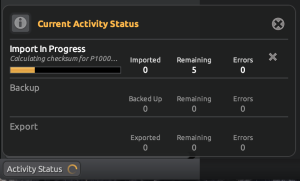

To streamline repetitive tasks, you can save presets that will remember your settings for future sessions.

To streamline repetitive tasks, you can save presets that will remember your settings for future sessions.