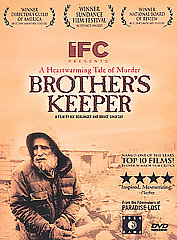

I became an instant Joe Berlinger fan about 10 minutes into watching his most recent film, Crude, which screened last fall for a week at the Varsity in Seattle. After watching that as-it-happens legal drama, which pitted native people in Ecuador against Chevron, I want to see everything this documentary filmmaker has ever done. First top: Brother’s Keeper, his first feature length documentary (which he co-directed with Bruce Sinofsky).

I became an instant Joe Berlinger fan about 10 minutes into watching his most recent film, Crude, which screened last fall for a week at the Varsity in Seattle. After watching that as-it-happens legal drama, which pitted native people in Ecuador against Chevron, I want to see everything this documentary filmmaker has ever done. First top: Brother’s Keeper, his first feature length documentary (which he co-directed with Bruce Sinofsky).

Crude was about a courtroom battle (with most of the action filmed outside of the courtroom) and so is Brother’s Keeper. But in both films, there’s not much tedious back-and-forth argument between attorneys in a courtroom. From a filmmaking perspective, what I found remarkable about Brother’s Keeper was the fact that the story builds like a Hollywood thriller toward a climax in the courtroom. Berlinger takes us into the lives of the defendant, a man accused of murdering his brother.

The film is classic verite. That makes sense given Sinofsky’s background – he worked as an editor for the verite pioneering Maysles brothers in New York before partnering with Berlinger in 1991 to create his own production company, Creative Thinking International. But what most impresses me the way Sinofsky and Berlinger put this film together is the care they must have taken in selecting which story to tell. All of the classic elements were there – this story was a major media event at the time, because it involved accusation of assisted suicide as well as murder, and the entire local community supported the accused. All the juicy elements of conflict were in place, so it really didn’t matter how the case went in court – it was going to be a good film no matter what. And that’s my big takeaway from this film: pick stories where the conflict is so great that people will stay on the train until it reaches its destination without getting off early.

The film appears to have been shot mostly from a shoulder mounted camera, which was on sticks a lot. There’s brief but frequent music use that helps creating a feeling for the place where the drama happens – down-home violin music which feels like a barn yard. I noticed also that they lit many of the interior scenes with one or two hot lights, in such a way that the lighting doesn’t call attention to itself.

You can hear the voice of the filmmakers frequently, asking the questions and interacting with the brothers. That works very well as an approach here, and something I’m tempted to try out myself. But the filmmakers do not enter the frame (although Berlinger at one point almost entered the frame and you can hear him protesting that he doesn’t want to “be in the film.”) Camera movement doesn’t call attention to the techniques being used – that is, no dolly moves or anything like that.

The way the film is structured, with pauses between the interview segments to show b-roll of the farm with ominous music chords works very well, before we go back to next interview. And we hear depositions from lawyers and prosecutors but we don’t SEE them until much later in the film, a very effective technique. This is a technique I’m going to use a LOT in my films because more than any single technique, showing one thing while hearing something else is a very powerful way to hold viewer’s attention and add a third layer of meaning to what’s being shown AND what’s being said. The sum is greater than the parts when this is done well.

Another interesting observation: they don’t ID the people portrayed, they just show them, and you have to guess who the person is based on the clues they provide and the context. This helps make it feel more like a narrative film, and less like a documentary, and I like it. Another thing that adds visual interest: virtually all of the people included in the film are OLD. Really old. And they look really interesting with the texture of their faces and the way they talk.

Traveling shots with brothers riding on tractor create a sense of the film being pulled forward and helps get us from one interview to the next. Part of the fun is the long sequences in which we hear filmmakers asking questions and hear the answers aparently without cuts, so it feels very real and immediate and trustworthy. Joe asks obvious and human questions, like “Didn’t you have a girlfriend? Why not?” One very important observation: the filmmakers do NOT stammer or have to restate their questions – they just ask them, simply and directly. They are good conversationalists with a lot of clarity in their speech. They ask a lot of simple, probing questions, such as “Why” and “Why not?”

The farmers do answer frequently in simple “yes” and “no” style, which normally doesn’t work for an interview, but which helps establish them as simple, salt-of-the-earth people, and partly explains why the filmmakers included themselves – because the simple answers need the voice of filmmaker for context to the question.

Great use of signs to establish where the action is happening – sign of state police before we find outselves in an interview with a police officer tells us that we are inside that building for the interview. We see the farmers continuing their simple life while the courtroom drama unfolds on the sound track. Nice cuts of people getting into car and driving away as a transition.

Finally, the climax of the film happens when the case goes to trial. The camera is allowed in the courtroom, and after the jury deliberates, they reach a verdict and we are on the edge of our seats as is every single person in the courtroom to see the result, which is the stuff of classic story climax. After that, the film wraps up very quickly – we see the main characters congratulated by members of the community, and the main character says “it feels like I’m going to start over again,” gets on a tractor, and rides off into the rest of his life. Nice way to tie it up.