Turn on your TV. What’s the first thing you see? Somebody talking to the camera. Blah blah blah. Open a film on Netflix. What’s the first thing you see? Action. The essence of cinematic storytelling is showing, not telling. So, if you aspire to cinematic storytelling with your documentary filmmaking, why film talking heads in the first place? Why not commit to showing instead of telling?

I’m a little hesitant to share this insight, because it’s valuable to me. Big medical organizations hire me to to tell their most important stories, and it’s a financially rewarding gig. Why give away my secret? But ideas are cheap – it’s execution that matters. So here’s a cheap idea that, when applied, has proven invaluable to me and my clients.

Stop shooting interviews with a camera.

Wait, what? How can you say that – aren’t you a camera guy? Yes, I am. But my first commitment is to story. And I’ve observed that:

- Being on camera feels like a performance to most people; being on mic feels more like a conversation. Talking heads are boring; mic’d conversations are more authentic.

- Cameras need lights, grip and crew. Sound needs only a mic, a recorder, and a quiet place, so audio costs less.

- If the audio interview doesn’t move you, you move on. It’s easy to do that because you’re less invested when you use a mic.

- Not having any interview footage forces you (and your client) to choose a visually interesting character who provides cinematic b-roll opportunities.

- Recording interviews audio-only adds a “radio edit” step to your editing workflow, building client buy-in early in the process. This translates into fewer client changes at the rough cut stage, faster delivery, and a happier client.

Let’s unpack this.

Talking heads are boring

Most people aren’t actors. So, they are uncomfortable when a camera is pointed at them. There are ways of minimizing this, but the simplest, most effective way is to simply nix the camera. Instead, bring only a microphone. That way, you can be sure they’re never thinking “how do I look?” But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

Great interviews are genuine, human conversations. And when cameras are not in the mix, everything gets easier. Not only for the subject, but also for me. No part of my brain is thinking about the lighting, or the frame rate, or the ISO. I’m just thinking about the person I’m talking to. I’m fully present. And THAT is the foundation of an extraordinary interview.

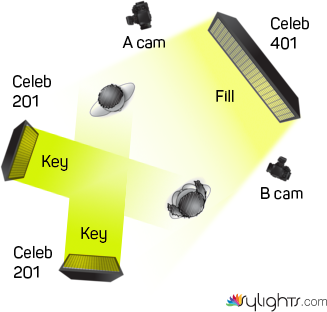

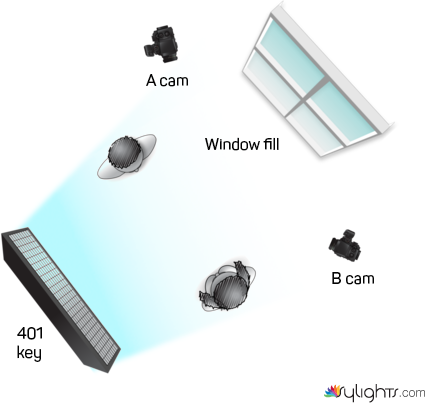

Camera interviews are expensive

In the large-nonprofit productions I do, a typical interview involves a crew of 3-4 people and a station wagon full of equipment. If we split the equipment up between picture and sound, about three-quarters of the “stuff” we bring belongs in the picture category. By going audio-only with your interviews, you eliminate three-quarters of your stuff. This also allows you to cut your crew in half. You see where I’m going with this: Cameras are expensive; talk is cheap.

Documentaries need casting, too

Great documentary films are built from great stories. Great stories emerge from great interviews. And great interviews come from great characters. To find great characters, you have to do casting.

When you use a mic for your interviews, you turn your interviews into casting sessions. If the interview is weak, it’s easy to move on to another story candidate without incurring the high costs of camera production. It allows you to cut your losses quickly.

On the other hand, if it’s an extraordinary interview, it’s easy to get your client to buy in to the story, with a radio edit. And the only thing left to do is the b-roll. More on that below.

It forces you (and your client) to choose wisely

Too often, clients settle. They settle for a boring character and an uninspiring story that has few b-roll options. They do this because you let them. And you let them by shooting interviews.

When you shoot an interview, you can always cover your lack of good b-roll by cutting to the talking head, like they do on TV. But no matter how well you’ve lit the interview, it’s still a talking head.

When you have no talking head, you force both yourself and your client to pick a strong character, who will provide you with action to film. That is, you force yourself to show instead of tell. That’s sometimes an uncomfortable place to be. But trust me, it’s a good place to be.

The radio edit advantage

We’ve all been there. You work really hard on an edit, you present it to your client, and you hold your breath. Will they like it? How many changes will they make? What if they don’t like it?

I have discovered that if you take the time to introduce your client to a story with a “radio edit,” you (and your client) will be able to breathe a lot easier when it comes time to deliver your rough cut.

A radio edit is an audio-only version of your film that would totally work if it were aired on the radio, including music and pacing. The first time I did this, the client came back to me with a surprising comment: “Wow. This sound like a This American Life piece. We can’t wait to see what it looks like with video!”

By giving them a polished radio edit first, you introducing them to your story gently. You invite them to buy in to the story, and to your approach. I find that clients have a few changes at this stage. But these few are much easier and less expensive for you to make than they would be after you’ve added b-roll.

Here’s how it works

On this project, my client needed help launching a $2 billion fundraising campaign. They wanted to find a story that would inspire their audience to believe that heart disease was beatable, and that their donations could have a direct impact. Because of the big numbers at stake, the approval chain included a lot of brass, including the CEO. Red flag!

The first person we interviewed (mic only) didn’t move us. Neither did the second person. So we kept looking. Then we found Jim. Here’s his radio edit:

The client liked the radio edit, and suggested some minor changes. Here’s the final film:

When they saw the rough cut (for this and another film we made concurrently using the same approach), they sent me this email:

Dan. I don’t think we have ever given this little feedback on videos. They’re universally loved, and we think they’re going to work really well.

Werner Herzog once said “Good footage always cuts.” The visuals don’t have to literally match the dialog (as long as you have great story as a foundation). Somehow by choosing a character who inhabits an interesting environment, who does interesting things, the footage will always cut.

So. Next time you’re faced with a high stakes interview-based project, consider how ditching your camera can help you do more with less.